2013 SF VBAC Statistics

UCSF and SFGH are leading the way with the best and most progressive VBAC care.

CPMC - 11% Yikes!!!

SFGH - 44.5%

Kaiser - 26%

UCSF - 37%

2013 SF VBAC Statistics

UCSF and SFGH are leading the way with the best and most progressive VBAC care.

CPMC - 11% Yikes!!!

SFGH - 44.5%

Kaiser - 26%

UCSF - 37%

Placenta Medicine as a Galactogogue

Full publication by Melissa Cole, IBCLC can be found HERE

Given the reality that there is little research when it comes to human placenta preparation and consumption, the ethical and legal issues around this topic must be explored further as well. Animal research has certainly shown that there are very real benefits for nonhuman mammalian placentophagy, especially when it comes to pain relief during/after labor and optimizing maternal– infant bonding (Apari & Rozsa, 2006; Kristal, 1980; Kristal et al., 2012). In addition, limited human research has shown some benefits, such as improved infant weight gain, increased supply in some cases, and overall maternal satisfaction with the practice. The possibilities for potential human applications regarding placenta ingestion certainly warrant a call for research. Although placenta medicine is still viewed as an obscure, fringe practice by many, some mothers are embracing it. As demand for this practice increases, researchers and healthcare professionals alike will have to invest more time and resources into studying human placentophagy so that we can better understand the clinical applications and risks versus benefits of this practice.

Delayed Cord Clamping and the Power of the Placenta

Children whose cords were cut more than three minutes after birth had slightly higher social skills and fine motor skills than those whose cords were cut within 10 seconds.

"There is growing evidence from a number of studies that all infants, those born at term and those born early, benefit from receiving extra blood from the placenta at birth," said Dr. Heike Rabe, a neonatologist at Brighton & Sussex Medical School in the U.K. Rabe's editorial accompanied the study published Tuesday in the journalJAMA Pediatrics.

Delaying the clamping of the cord allows more blood to transfer from the placenta to the infant, sometimes increasing the infant's blood volume by up to a third. The iron in the blood increases infants' iron storage, and iron is essential for healthy brain development.

Read the full NPR article HERE

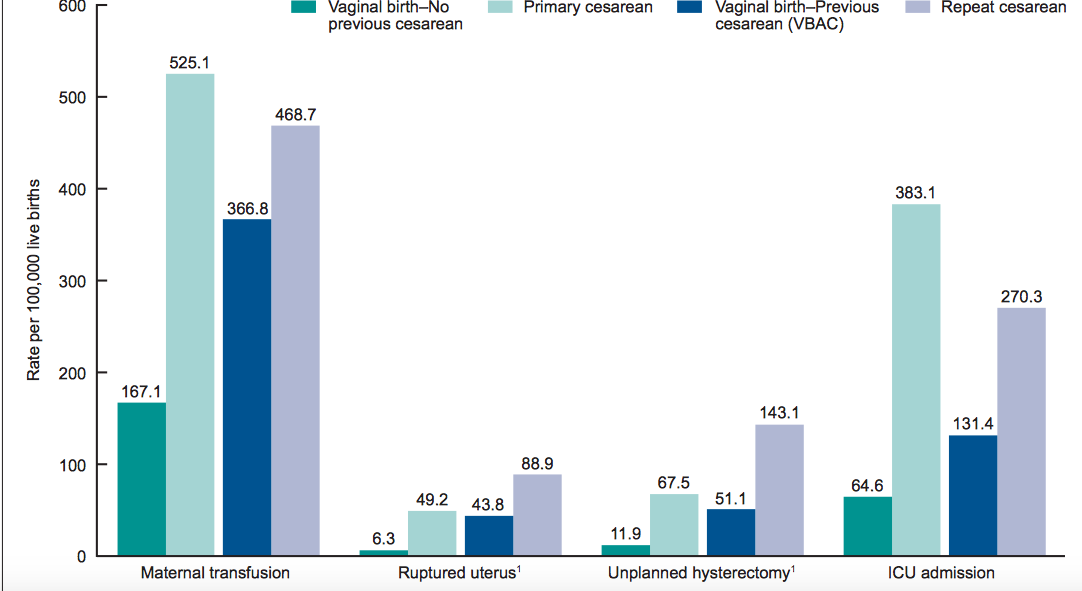

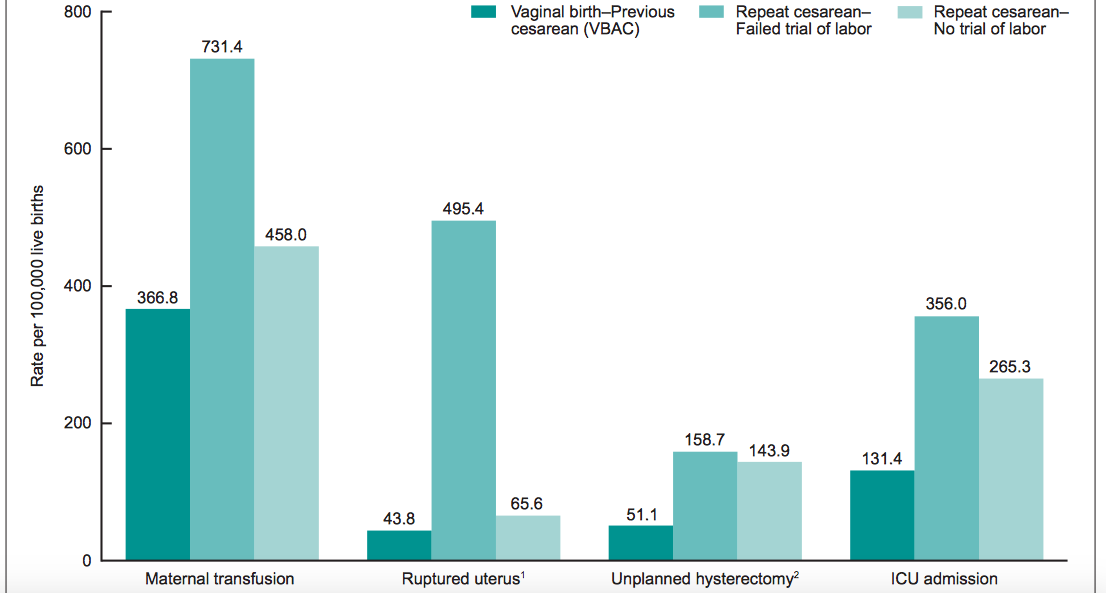

CDC Study: Vaginal births are much safer for first timers and VBAC births

U.S. Report on Maternal Morbidity for Vaginal & Cesarean Delivery by Henci Goer and the CDC

A "must read," the CDC has published an analysis of severe maternal morbidity (transfusion, ruptured uterus, unplanned hysterectomy, Intensive Care Unit admission) in U.S. women according to mode of delivery and previous cesarean history. As the bar graphs from the report make clear, the glaringly obvious take-home is that clinicians should strive for vaginal birth whenever safely possible, whether that be a first vaginal birth or a VBAC.

READ THE FULL REPORT HERE

Maternal morbidity for women with no previous cesarean delivery, by method of delivery and trial of labor: 41-state and District of Columbia reporting area, 2013

Maternal morbidity for women with a previous cesarean delivery, by method of delivery and trial of labor: 41-state and District of Columbia reporting area, 2013

$40 million for study of human placentas

The Human Placenta Project, launched last year by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) despite uncertainty over how much money would back in the effort, has just received a whopping $41.5 million in 2015 to study the vital mass of tissue that sustains a developing fetus.

The placenta carries nutrients and oxygen to a fetus from its mother’s bloodstream and removes waste; problems with its performance may contribute to health concerns ranging from preterm birth to adult diabetes. Yet it is the least understood human organ.

The Ups and Downs of New DNA Testing

See the full article here.

Ultrasound is often used for prenatal screening. It's just one of several prenatal screenings available to pregnant women.

When Amy Seitz got pregnant with her second child last year, she knew that being 35 years old meant there was an increased chance of chromosomal disorders like Down syndrome. She wanted to be screened, and she knew just what kind of screening she wanted — a test that's so new, some women and doctors don't quite realize what they've signed up for.

This kind of test , called cell free fetal DNA testing, uses a simple blood sample from an expectant mother to analyze bits of fetal DNA that have leaked into her bloodstream. It's only been on the market since October 2011 and is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration — the FDA does not regulate this type of genetic testing service. Several companies now offer the test, including Sequenom andIllumina. Insurance coverage varies, and doctors often only offer this testing to women at higher risk because of things like advanced maternal age.

"I think that I initially heard about it through family and friends," says Seitz. "They had had the option of it given to them by their doctors."

To her, it sounded great. She didn't want an invasive procedure like amniocentesis orchorionic villus sampling.Those are considered the gold standard for prenatal genetic testing, but doctors must put a needle into the womb to collect cells that contain fetal DNA, which means a small risk of miscarriage.

During amniocentesis, a needle is inserted through a woman's abdomen into the amniotic sac. A sample of fluid is extracted and screened for genetic disorders such as Down syndrome.

"I wasn't interested in going as far as getting an amniocentesis because of the risk associated with that," she explains, "and so when I heard about this test, that was part of the reason that I was most interested in it."

This new way of testing fetal DNA seemed to have already become fairly common where Seitz used to live, in Washington, D.C. But she had recently moved to Alabama, and the clinic she went to there wasn't as familiar with it — although when she talked to her doctor, she learned the clinic had just had a visit from a company's sales representative.

"I think it was a fairly new test for them at that point, but she was interested in pursuing it further to see what needed to be done," Seitz says.

Seitz got her blood drawn last July, becoming one of hundreds of thousands of pregnant women who've opted for this new kind of test instead of the more traditional, invasive ones. Doctors say the impact has been huge.

"Those of us in the field who do diagnostic procedures like CVS and amnio have seen a drastic decrease in the number of those procedures that are being performed," says Dr. Mary Norton, an expert on maternal-fetal medicine and genetics at the University of California, San Francisco. "Places are reporting doing fewer than half the number of procedures that were being done previously."

But, she says, things have changed so quickly that it may be hard for doctors and patients to know what they're dealing with.

"It's still new and it's quite different than previous genetic testing that's been available," says Norton. "It's quite a different paradigm, if you will."

An invasive test like amniocentesis or CVS lets doctors get a complete picture of the chromosomes and a solid diagnosis.

Until the new testing technology came along, the only less invasive option was for an expectant mother to get an ultrasound, plus have her blood tested for specific proteins. This can reveal if there's an increased risk of certain disorders, but it's not very accurate and produces a lot of false alarms.

Studies have shown that the new fetal DNA tests do a better job, says Norton. They're less likely to flag a normal pregnancy as high risk.

"They're much more accurate than current screening tests, but they are not diagnostic tests in the sense that amniocentesis is," says Norton, "and so I think that has led to some confusion."

Even though the newer blood tests do look at fetal DNA, they can't give a definitive answer like an amniocentesis can because they're analyzing scraps of fetal DNA in the mother's blood that are all mixed up with her own DNA.

Norton says when women get worrisome results from one of these new tests and are referred to her center, they sometimes don't understand why doctors are offering a follow-up amnio "because they were under the impression that this was as good as an amnio."

She is concerned that some people might end a pregnancy without getting confirmatory testing and points to one study last year that found a small number of women did that.

"There's at least some evidence that it's happening to a greater degree than I think many of us are comfortable with," she says.

The tests are being used more and more widely. Some worry that the companies' websites and marketing materials don't make the limitations clear enough.

But Dr. Lee Shulman doesn't see it that way. He's an obstetrician and geneticist at Northwestern University in Chicago who has consulted for a couple of the testing firms.

"Patients need to understand that while this is better, it is not a diagnostic test, and I think the companies have done a great job in putting this material out," he says. "Whether or not clinicians use this material and take it to heart and use it for patient counseling is a different story."

He says the technology is so new that a lot of doctors have no experience with it, and consumers need to understand that.

"If the patient, if the couple, are not getting the answers, not getting the information they feel comfortable with, they need to seek out prenatal diagnostic centers, maternal fetal specialists, clinical geneticists, who may have more experience," says Shulman.

For example, here's one thing that might turn out to be a little more complicated than would-be parents might expect. Along with screening for the common chromosomal disorders, companies offer parents the chance to learn their baby's sex — weeks before it's clear on a sonogram.

"Many women are very excited by the idea that as part of their blood testing, they could find out pretty definitively if the baby is a boy or a girl," says Dr. Diana Bianchi, an expert on prenatal diagnostics at Tufts University School of Medicine.

What they may not realize, she says, is that the test will also determine whether there's something abnormal about the sex chromosomes.

"Approximately 1 in 700 pregnancies there's an extra X or extra Y," she says, noting that these are mild conditions that would normally go undetected, unless a woman had an invasive test like an amnio. Some babies with these conditions grow up into adulthood and never know they have them, unless they face a symptom like infertility.

Seitz, in Alabama, thought it was a bonus that getting this new blood test would tell her if she was having a boy or a girl. But it actually didn't do that, because of a paperwork glitch.

"The box for sex got unchecked somewhere along the way, so we weren't able to find it out from the test," says Seitz, who learned from an ultrasound that she was having a girl. The results she did get from the fetal DNA test were reassuring.

Waiting till the placenta is birthed to clamp the cord.

Educate yourself. Knowledge is power.

Delayed Cord Clamping

What is the Evidence for Inducing Labor if Your Water Breaks at Term?

What is the Evidence for Inducing Labor if Your Water Breaks at Term?

By Alicia A. Breakey, MA, PhD Candidate, Angela Reidner, MS, CNM, and Rebecca Dekker, PhD, RN, APRN

What is PROM?

Prelabor or “premature” rupture of membranes (PROM), happens when your water breaks before the start of labor.

Term PROM is when your water breaks before labor at ≥37 weeks of pregnancy.

Preterm PROM, or PPROM, happens when your water breaks before 37 weeks.

In this article, we are going to focus on Term PROM.

This article was published November 20, 2014

How many women experience term PROM?

Estimates vary, but researchers say that about 8-10%, or 1 in 10 women, will have their water break before the onset of labor (Gunn et al., 1970).

Where did the “24 hour clock?” come from?

Many people are under the impression that once a woman’s water breaks, she only has 24 hours to give birth or she will automatically need a C-section. Where did this opinion come from? Is it evidence-based?

The concept of the 24-hour clock actually started in the 1950s and 1960s.

Back then, babies were more likely to die the longer their mother’s water was broken after PROM (Lanier et al., 1965; Calkins, 1952; Taylor et al., 1961; Burchell, 1964).

Many doctors at this time said that women should give birth within 24 hours after their water broke, even if that requires a C-section.

In 1966, Shubeck et al wrote,

“With rupture of membranes, the clock of infection starts to tick; from this point on isolation and protection of the fetus from external microorganisms virtually ceases…Fetal mortality, largely due to infection, increases with the time from rupture of membranes to the onset of labor.” (Shubeck et al., 1966)

When we looked at these classic articles, we too were struck by the large increase in the risk of stillbirth and newborn death the longer a mother’s water was broken after PROM. One study found that as many as 50% of babies were stillborn or died after birth if their mothers developed a fever or had other signs of infection with PROM (Lanier et al., 1965).

No wonder doctors were so afraid of long periods between the water breaking and birth! In some studies, taking more than 24 hours for the baby to be born led to death rates that were 2 or 3 times higher than babies who were born within 24 hours after PROM!

However, it is important to understand the differences between how women were cared for in the 1950s and 1960s and how they are cared for today—nearly 70 years later.

First of all, nearly all of the studies back then had overall death rates that would be considered completely unacceptable today. Whether or not a mother experienced PROM, the overall stillbirth and newborn death rates in these studies were as high as 4% for hospital births.

The researchers did not usually report the number of breech births, C-sections, and use of forceps during birth. Several babies died from “maceration”—possibly from botched forceps deliveries. Because Cesareans were so uncommon back then, women who needed C-sections to save their babies often did not have them.

One study mentioned that more than half of the mothers were African American. At that time, African American women were considered “charity” patients, and it is likely that many of them received no prenatal care. They often came to the hospital many hours after their water had been broken, with no care up until that point (Lanier et al., 1965). The chance of infection was 5 times greater in this group of women compared to the private patients.

In many of these papers, the authors mentioned that antibiotic treatment was out of vogue during this time. This means that many women who were at risk for infections or had early symptoms of infection were not treated until their infections were quite severe. These mothers could pass on those infections to their babies. If doctors did use antibiotics, they were usually limited to only penicillin, which is not effective against many types of bacteria.

Also, Group B strep in the mother—an important risk factor for newborn infections—was not understood or treated at that time.

Another reason reported death rates were high back then was because some researchers did not separate term PROM from preterm PROM. In other words, they put all babies who were born after PROM in the same group—whether or not they were born prematurely. However, when they did separate the normal birth weight babies from the low birth weight babies, they still found that normal birth weight babies had higher death rates after 24 hours of PROM than normal babies who were born within 24 hours of PROM.

Finally, most of the studies from the 1950s-1960s were based on retrospective (looking back in time) chart reviews. This type of study can have problems with accuracy. Also, none of the researchers looked at how many vaginal exams these women had—one of the most important risk factors for infection with PROM.

Today, we have access to better quality research about what happens when women wait for labor to start on its own or induce labor after term PROM.

This research shows that with proper care, waiting for up to 48-72 hours after the water breaks does not increase the risk of infection to babies who are born to mothers that meet certain criteria.* However, waiting means that women may have a higher chance of experiencing infection themselves (Hannah et al., 1996; Pintucci et al., 2014).

So the “24-hour clock” rule is no longer valid today.

*These criteria are important and we will talk more about them at the end of the article.

If you have PROM, how long does it take for labor to start on its own?

If women with PROM are not induced, around 45% will go into labor within 12 hours (Shalev et al., 1995; Zlatnik, 1992).

Between 77% and 95% will go into labor within 24 hours of their water breaking (Conway et al., 1984; Pintucci et al., 2014; Zlatnik, 1992).

In a recent large study, 76.5% of women with term PROM went into labor within 24 hours, and 90% were in labor within 48 hours (Pintucci et al., 2014). Although some of these women (16%) were induced, most (84%) went into labor on their own.

In another large study, researchers assigned some women to wait for up to 72 hours for labor to begin after their water broke. Out of these women, 83% went into labor on their own and had a normal vaginal birth (Shalev et al., 1995).

Some researchers have found that it may take longer for women giving birth for the first time to go into labor after their water breaks. One study found that 20% of women giving birth for the first time waited longer than 48 hours for contractions to begin after PROM, while only 7% of women who had given birth before took longer than 48 hours after PROM (Morales & Lazar, 1986).

What could cause your water to break before labor?

Microbes (bacteria and yeast)

In looking for causes of Term PROM some studies have looked at the microbes in women’s vaginas.

The question is—are there types of microbes in a woman’s vagina that put her at higher risk for PROM?

In one study (Veleminsky & Tosner, 2008), researchers found that more women who experienced term PROM had a yeast infection than women who did not have term PROM.

Also, women who did not have term PROM were more likely to have lactobacillus (the good bacteria of the vagina). So it’s possible that having “good bacteria” in the vagina may help protect women from PROM.

Vaginal exams

As women get closer to their due date, many providers will check the cervix vaginally (vaginal exams) starting at around 35-37 wks. Some will continue these checks weekly until birth.

In 1984, a study by Lenihan clearly showed a relationship between weekly vaginal exams and PROM. In this study, 349 women were randomly assigned to weekly vaginal exams starting at 37 weeks, or no vaginal exams until after 40-41 weeks.

The group with weekly vaginal exams starting at 37 weeks had a three times higher chance of having PROM (18%) compared to 6% of women who had no weekly exams until 40 or 41 weeks (Lenihan, 1984).

In another study that took place in in 1992, 587 women were randomly assigned to weekly vaginal exams or no exams. They found no differences in the rates of PROM between the two groups. While they concluded there was no relationship between antenatal vaginal exams and term PROM, they also noted no benefit to the weekly exams (McDuffie et al., 1992).

Sweeping of the membranes

There is some evidence that sweeping (stripping) the membranes is related to an increased risk of term PROM.

In one study, 300 women were randomly assigned to have either a cervical exam (control group) or membrane sweeping weekly starting at 38 weeks (Hill et al., 2008). If a finger could not be put through the cervix (because the cervix was less than 1 centimeter dilated), women in the membrane sweeping group were given cervical massage instead, to encourage dilation. So women in the membrane sweeping group did not always receive membrane sweeping.

For both groups as a whole, there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of PROM (7% in the no-sweep group vs. 12% in the sweeping group). When we say that something is not “statistically significant,” this means that the differences could have been due to chance.

A few women went into labor or had PROM after they were randomized but before they received their assigned intervention at 38 weeks. When these women were kept out of the analysis, the rates of PROM were 10.3% in the sweep group and 5% in the non-sweep group. This was still not statistically significant.

However, for women who were more than 1 centimeter dilated at the time of the intervention, women in the membrane sweeping group were significantly more likely to develop PROM (9.1% vs. 0%).

This is important because these are the women who actually received membrane sweeping, instead of cervical massage.

Rates of maternal infection (chorioamnionitis) were similar between the two groups, for both GBS-negative and GBS-positive women.

Unfortunately, there have been no studies that have compared membrane sweeping to having no vaginal exams at all. Since there is evidence that vaginal exams—by themselves—can increase the risk of PROM, it would be interesting to know the risk of membrane sweeping compared to no interventions at all.

Vitamin C

There is a theory that Vitamin C can strengthen the membranes and prevent them from breaking early. However, only one study has found that Vitamin C may prevent PROM, while two studies have found that it may actually increase the risk of PROM.

In a small but high-quality trial that took place in Mexico, 109 pregnant women were randomly assigned to receive Vitamin C 100 mg once per day or an identical-looking placebo pill, starting at 20 weeks. Women could not be in the study if they were taking any other prenatal vitamins.

One in four women in the placebo group (25%) experienced PROM, compared to only 8% of the Vitamin C group (Casanueva et al., 2005).

It’s important to note that the Vitamin C dose in this study (100 mg) was small—much lower than the highest recommended amount of 2,000 mg per day. The researchers warned that taking high doses of Vitamin C could possibly increase the risk of PROM.

In fact, in 2008 and then again in 2010, researchers found a link between high doses of Vitamin C (when given with Vitamin E) and PROM (Spinnato et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010).

The first of these studies randomly assigned 697 pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia to take Vitamin C (1,000 mg) and Vitamin E (100 IU) once per day, or to take a placebo daily. Women assigned to the Vitamin C/E group had a two times higher risk of PROM (10.6% vs. 5.5%) compared to women who took a placebo (Spinnato et al., 2008).

In 2010, another group of researchers randomly assigned 2,647 low-risk and high-risk women to Vitamin C (1,000 mg) and Vitamin E (400 IU) twice per day, or to take a placebo. The trial was stopped early because they found that women who took Vitamin C and E were at increased risk of stillbirth or newborn death(1.69% vs. 0.78%), PROM (10.2% vs. 6.2%) and preterm PROM (6% vs. 3%) compared to women who took a placebo (Xu et al., 2010).

Researchers aren’t sure why one study found a beneficial effect of Vitamin C, and two studies on Vitamin C found harmful effects.

In the one study that found benefits, a small group of low-risk pregnant women received a small dose of Vitamin C (100 mg) and no other vitamins.

In the other studies that found evidence of harm, both low- and high-risk women received high doses of both Vitamin C and Vitamin E together. It could be that higher doses increase the risk of PROM, or maybe taking Vitamin C and E together increased the risk of harm.

Ideally, it would have been better if these studies had looked at four groups: one group that took Vitamin C, one group that took Vitamin E, one group that took Vitamin C and E, and one group that took a placebo. But, we do not have that information, and we probably never will. Because the Vitamin C/E was harmful in high doses, it would not be ethical to do another study to figure out WHICH vitamin was harmful.

As an FYI, a common prenatal vitamin may contain about 60 mg of Vitamin C and 30 IU of Vitamin E, much smaller doses than the Vitamins tested in these 2 studies that found evidence of harm.

Fatty acid supplements

Omega-3 fatty acids, which are commonly found in fish oils, may be able to lower inflammation. This decrease in inflammation could delay the inevitable increase in prostaglandins that leads to weakening of the fetal membranes, cervical dilation and labor contractions.

In 2014, researchers randomly assigned 129 women to receive 200 mg of DHA (Omega 3 fatty acids) daily and 126 to receive a placebo with olive oil from the 8th week of pregnancy until birth (Pietrantoni et al., 2014).

They found a link between DHA supplementation and a decrease in biochemical markers for inflammation—as well as fewer cases of PROM.

Women who received the DHA supplements were less likely to experience term or preterm PROM. Preterm PROM was experienced by 1 woman in the DHA group and 4 women in the placebo group. Term PROM was experienced by 5 women in the DHA group and 12 women in the placebo group.

Other risk factors for term PROM

Most of the evidence on preventing PROM focuses entirely on the prevention of preterm PROM (before 37 weeks).

We did not find any other studies on dietary methods of preventing term PROM, such as eating eggs or high levels of protein. This is an area where more research is needed.

Is term PROM sometimes a normal, physiological event?

In some cases, it is possible that prelabor rupture of membranes at term is normal. Fetal membranes are “programmed” to weaken toward the end of labor.

A combination of factors leads to the creation of a weak spot in the amniotic sac near the cervix. Certain inflammatory reactions of the immune system can make this process go faster, which is why a prenatal infection can lead to prelabor rupture of the membranes.

Most commonly, the pressure of contractions causes the membranes to finally give way at the weak spot, but occasionally this can happen before contractions begin(Moore et al., 2006).

Induction versus Waiting for Labor

When a woman’s water breaks before labor at term, one of the most important questions she will face is whether to induce labor or wait for labor to start on its own.

Waiting for labor to start on its own is called “expectant management.”

Starting labor artificially with induction is called “active management.”

Many researchers have tried to compare the risks and benefits of induction versus expectant management.

In almost all of the studies on this issue, researchers only looked at women with PROM who had a single baby in head-first position. And they usually did not allow women with other pregnancy complications, such as high blood pressure and gestational diabetes, in their studies.

So the results that we will talk about in this article apply mainly to low-risk women.

When researchers compare induction versus expectant management, they usually look at these health results:

- How long it took for the baby to be born after PROM

- How often mothers experienced chorioamnionitis (infection of the membranes, or amniotic sac)

- How many women had C-sections

- How many babies had infections (either actual infections or suspected infections)

Cautions about the Evidence

The evidence on induction versus waiting for labor with term PROM is hard to interpret. This is because each research study set its own standards for how labor was induced, how long mothers waited for labor to begin before being induced, and under what conditions women required a C-section. These differences can lead to very different findings among studies that are supposed to be answering the same question.

One of the most important problems with the evidence on term PROM is related to Group B Strep. Almost all of the studies that we will talk about, including the famous “TermPROM” study (Hannah et al., 1996), were carried out before women in the U.S. had Group B strep screening and were offered antibioticsif they were positive for GBS.

It is very common for mothers to carry Group B Strep bacteria in their digestive systems. The CDC reports that 25% of women will carry the Group B Strep bacteria in their vaginas or rectums. Carrying this type of bacteria puts women at higher risk for chorioamnionitis (infection of the membranes) and puts newborns at higher risk for Group B Strep infection.

Currently, most women in the U.S. and some other countries are screened for GBS in the third trimester, and if they are positive for GBS, most receive IV antibiotics when labor begins.

Screening and treatment for GBS did not happen in virtually all of the studies that looked at induction versus waiting for labor with term PROM. So the results from these studies probably overestimate the risk of infection that a mother or newborn might experience if she had term PROM today.

You can read more about GBS here: http://evidencebasedbirth.com/groupbstrep/

Ultimately, the question “What should a mother do if her water breaks before labor at term: Is induction or waiting for labor the better choice?” will remain controversial until another large-scale study is conducted using modern methods of screening and treating for Group B Strep bacteria.

The Famous TermPROM Study

The most important study that has ever been done on term PROM is the “TermPROM” study. This high-quality study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Hannah et al., 1996).

Because it was such a large study, the TermPROM results drive most of the findings in any meta-analysis, including the Cochrane review on this topic (Dare et al., 2006).

Therefore, we will focus on the findings of the TermPROM study in this article, while occasionally mentioning results from other studies.

Between the years of 1992-1995, a group of researchers from 72 hospitals enrolled 5,041 low-risk women from six different countries (Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, Israel, Sweden, and Denmark) into the TermPROM study.

Women were invited to be in the study if they came to the hospital with PROM. All women had a non-stress test before entering the study, and they were not included in the study if they had meconium staining of the amniotic fluid or any signs of infection when they arrived at the hospital.

All women were swabbed to check for Group B strep when they entered the study, but in most cases the doctors and women did not know the results of the GBS test until after the baby was born.

Women with term PROM were randomly assigned to one of four groups:

- Immediate induction of labor with synthetic oxytocin

- Immediate induction of labor with prostaglandin gel (PGE2)

- Waiting for labor to start for up to four days, followed by induction with oxytocin if needed

- Waiting for labor to start for up to four days, followed by induction with prostaglandin gel if needed

Women who were assigned to the waiting groups could wait for labor to begin either at home or in the hospital. They were told to check their temperatures twice per day and were told to report any fever, change in the color or smell of the amniotic fluid, or other problems.

Women in the waiting (also called “expectant management”) groups were induced if they developed complications (such as signs of infection in the mother), if the mother requested an induction (which ended up being the most common reason for induction in the expectant management groups), or if labor did not start after four days.

Decisions about antibiotics were made by each woman’s healthcare provider.

What did researchers find in the TermPROM study and in other studies?

Cesarean Rates

In the TermPROM study, there were no differences in C-section rates between the induction groups and the waiting for labor groups. Cesarean rates were low in all four groups (13.7%-15.2%).

When the researchers separated out women who had given birth versus those who were giving birth for the first time, they still found no differences between groups.

Among women who were giving birth for the first times, the Cesarean rates were:

- 14.1% in the induction with oxytocin group

- 13.7% in the expectant management oxytocin group

- 13.7% in the induction with prostaglandin group

- 15.2% in the expectant management with prostaglandin group

Among women who had given birth before, the Cesarean rates were:

- 4.3% in the induction with oxytocin group

- 3.9% in the expectant management oxytocin group

- 3.5% in the induction with prostaglandin group

- 4.6% in the expectant management with prostaglandin group

About 1 in 4 of women giving birth for the first time had forceps or vacuums used during their births. Among women who had given birth before, only 3.4-4.6% had forceps or vacuums used. There were no differences between induction and expectant management groups in rates of forceps or vacuum deliveries.

Most other studies that compare the rates of Cesarean section in induction vs. expectant management found no difference in C-section rates.

Out of the 14 studies where researchers compared C-section rates between women who were immediately induced and those who waited for labor to begin on its own (See our Annotated Bibliography), nine found no difference in Cesarean rates, two found higher rates of Cesarean in the immediate induction groups, and three found higher rates of Cesarean in the expectant management groups (including one study of women with unfavorable cervices that allowed Cesarean upon maternal request if labor had not begun after 24h of expectant management (Ayaz et al., 2008).

Infection in the Mother

Mothers whose water breaks before they go into labor are at higher risk for infection.

The chorioamnion (or membrane) is a physical barrier to bacterial invasion during pregnancy, so when the water or membranes break, this means the mother is at higher risk for infection.

Chorioamnionitis means inflammation of the membranes due to infection.

For the rest of this article, we will refer to this condition as chorio.

In the TermPROM study, the researchers defined chorio as:

- Mother’s temperature >37.5° Celsius (99.5° Farenheit) on at least two time points more than one hour apart OR

- Any single temperature >38° Celsius (100.4° F) OR

- A white blood cell count of >20,000 per mm3 (normal = 4,500-10,000) OR

- Foul smelling amniotic fluid

Researchers today are pretty consistent in their criticism of the TermPROM definition of chorio for being “too loose.” This means that the TermPROM researchers probably over-diagnosed mothers with chorio.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, chorio can be diagnosed if a mother has a temperature > 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 F) AND usually at least one other indicator: fast fetal heart rate, fast maternal heart rate, abdominal pain, high white blood cell count, or foul smelling fluid.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has even stricter standards for diagnosing chorio: a mother’s temperature of >38 degrees Celsius (100.4 F) AND at least TWO other indicators: fast fetal heart rate, fast maternal heart rate, abdominal pain, high white blood cell count, or foul smelling fluid.

Using their looser definition of chorio, the TermPROM researchers found that chorio was less common in the immediate induction with oxytocin group (4%) compared to the group that waited for up to four days until induction with oxytocin (8.6%).

There were no differences in rates of chorio between women in the immediate induction with prostaglandins group compared to women in the waiting for labor for up to four days until induction with prostaglandins group.

The overall rate of chorioamnionitis in the TermPROM study was 6.7% (Seaward et al., 1997). This is a pretty high rate, and could be partially explained by the fact that very few women in the study had antibiotics for group B strep—a known risk factor for chorio.

In 2014, researchers published a large study that followed women who had term PROM, and they found that with screening and treatment for GBS, the overall rate of chorio was 1.2% in a sample that included many women who waited for labor to begin on its own (Pintucci et al., 2014).

When we look at the TermPROM study, there are several potential reasons—other than the induction itself—that could help explain why women in the immediate induction with oxytocin group had lower rates of chorio:

Women in the immediate induction group had fewer vaginal exams, shorter labors, and spent less time in the hospital compared to women in the waiting group.

When we looked at other studies that examined infection (See Annotated Bibliography), most researchers found that induction is associated with a lower risk of infection in the mother.

However it is very important to note that most of these studies do not take into account the number of vaginal exams, or they do not follow current GBS infection protocols(including the TermPROM study, which has been very influential on practice in the US).

Vaginal Exams

The number of vaginal exams that a woman has after her water breaks is a very important (possibly the most important) predictor of whether a woman with term PROM will develop chorioamnionitis.

In the TermPROM study, a higher percentage of women in the waiting for labor groups (56%) had four or more vaginal exams compared to women in the immediate induction groups (49%).

Seaward and colleagues found that in the TermPROM study, a woman’s risk of chorio increased as the number of vaginal exams that she received increased (Seaward et al., 1997).

Compared to women who had fewer than three vaginal exams:

- Women who had 3-4 exams had 2 times the odds of having chorio

- Women who had 5-6 exams had 2.6 times the odds of having chorio

- Women who had 7-8 exams had 3.8 times the odds of having chorio

- Women who had >8 vaginal exams had 5 times the odds of having chorio

The strong link between the number of vaginal exams and a mother’s risk of chorio has been confirmed in many other studies. For example, in 2004, Ezra et al. found that seven or more vaginal exams were an important risk factor for infection in women whose water had broken (Ezra et al., 2004).

The reason vaginal exams can lead to infection is because even though care providers use sterile gloves, their fingers are pushing bacteria from the outside of the vagina up to the cervix as they conduct the exam. In fact, vaginal exams have been shown to nearly double the number of types of bacteria at the cervix (Imseis et al., 1999).

There is some evidence that a “sterile speculum exam” does not introduce extra bacteria to the cervix. In one small research study, five women had two sterile speculum exams, and their cervixes were swabbed to check for bacteria after each exam. There was no increase in bacteria on the cervix after the second speculum exam (Imseis et al., 1999).

In the TermPROM study, about two in five women (40%) received a vaginal exam (with sterile gloved hands) when they entered into the study. This is important because the women who were in the waiting groups took longer to give birth than women who were induced with oxytocin. This means that women in the waiting groups were more likely to develop an infection purely based on this first vaginal exam (Seaward et al., 1997).

Time to Give Birth

Not surprisingly, the TermPROM study found that women who are induced give birth more quickly than women who wait for labor to start on its own.

Women in the immediate induction with oxytocin group gave birth an average of 17 hours after their water broke, and women in the immediate induction with prostaglandins group gave birth an average of 23 hours after their water broke—compared to an average of 33 hours in women in the waiting groups.

Cord prolapse

There was no evidence that term PROM increases the risk of cord prolapse.

Cord prolapse only occurred two times out of more than 5,000 women with PROM who were enrolled in the study—once in the induction group and once in the waiting group.

To read more about cord prolapse and whether or not bed rest is required with term PROM, read this article from Evidence Based Birth.

Newborn Infection

In the TermPROM study, blood samples were taken from most of the babies. There were no differences in newborn infection rates between any of the groups. Infection rates ranged from 2%-3%.

The TermPROM researchers carefully defined what an infection would be and even had separate doctors evaluate for newborn infection. Definite infection was defined as the presence of signs and symptoms of infection, plus one or more of the following: positive culture of blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, tracheal aspirate, or lung tissue; a positive Gram’s stain of cerebrospinal fluid; a positive antigen-detection test with blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or urine; a chest x-ray consistent with pneumonia, or a tissue sample diagnosis of pneumonia. Blood samples were taken for culture in 80% of the babies in all four groups.

Similarly, most other studies have found no difference in rates of infection or most other newborn outcomes (see Annotated Bibliography).

Of the ten studies that compared rates of newborn infection between induction and expectant management groups, nine found no difference and one found a higher rate of infection among those infants whose mothers had expectant management.

Three studies found no difference in rates of antibiotic use in neonates, while one study found that infants who were born to expectantly managed mothers were more likely to be given antibiotics after birth.

Other factors were related to an infant’s risk of developing an infection. These important risk factors for newborn infection included:

- A higher number of vaginal exams (Pintucci et al., 2014; Seaward et al., 1998)

- Mother carries Group B Strep (Pintucci et al., 2014; Hannah et al., 1997), (although the Hannah study did not use modern GBS screening and prophylactic antibiotics)

- Having a mother who developed chorio during labor (Pintucci et al., 2014; Seaward et al., 1998).

- Mothers whose labor took longer than 48 hours to start (Seaward et al., 1998).

In some studies, mothers whose labor took longer to start after their water broke were more likely to have newborns who were admitted to the NICU, or having a longer stay in the NICU (Akyol et al., 1999; Hallak & Bottoms, 1999; Hannah et al., 1996). It was not clear if this was because care providers were being more cautious with these infants.

Importantly, none of the studies with this or related findings used current Group B Strep antibiotic protocols.

Newborn Death

In the TermPROM study, there were no statistical differences in stillbirths or newborn deaths between the groups.

Despite the fact that the study had a sample of over 5,000 mothers, it was still not a large enough study to tell a statistical difference in deaths.

Because stillbirths and newborn deaths are such a rare event, you would need more than 28,000 women in a randomized trial to tell a difference in mortality rates between groups

However, there were four deaths not related to birth defects in the TermPROM study. There were two deaths in the expectant management oxytocin group and two deaths in the expectant management prostaglandins group, and zero deaths in the induction groups.

The fact that these deaths all occurred in the two waiting groups could have been due to chance, or it could have been related to the waiting for labor to begin. Because the study was not big enough to tell differences in death rates, we will never know the answer to that question.

- A 41-week baby was stillborn after 14 hours of waiting for labor in the hospital. Labor was induced after fetal heart tones disappeared. Death was caused by asphyxia (lack of oxygen to the baby).

- A 39-week baby was stillborn after 19 hours of waiting for labor in the hospital. The fetal heart tones disappeared shortly before labor began on its own. Death was due to Group B Strep infection.

- A 37-week baby died after birth following three days of waiting for labor at home. Labor was induced electively, and after showing signs of fetal distress, the baby was born by a difficult C-section that included the use of forceps. The baby died from birth trauma.

- A 40-week baby died after birth following 28 hours of waiting for labor at home. Labor began spontaneously, but the baby was born by C-section five hours later due to fetal distress. The cause of death was asphyxia.

Other newborn outcomes

In the TermPROM study, there were no differences between groups in the following newborn health issues:

- Apgar scores

- Need for resuscitation

- Seizures due to low oxygen levels

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Abnormal feeding at 48 hours

Fewer babies in the oxytocin induction group (7.5%) had to take antibiotics compared to the waiting for labor group (13.7%), even though there was no difference in infections. This may be because mothers in the waiting group were more likely to have chorio, and it is quite common for babies to receive antibiotics if their mother experienced chorio.

Babies in the oxytocin induction group were also less likely to have a >24 hour stay in the NICU (6.6%) compared to the expectant management oxytocin group (11.6%).

The researchers suggested that these longer NICU stays might have happened because care providers are more worried about infants born to mothers with prolonged rupture of membranes and want to provide more monitoring for them.

Satisfaction

In the TermPROM study, mothers in the oxytocin induction group were less likely to say that there was nothing they liked about their treatment (5.9% vs. 13.7%) compared to women in the expectant management oxytocin group.

Likewise, fewer women in the induction with prostaglandin group said there was “nothing they liked about their treatment” (5.1% compared to 11.7%) compared to women in the expectant management prostaglandin group.

In other words, rates of satisfaction were high in both groups, but higher in the induction groups.

If women choose to wait for labor to start on its own, is there any evidence that it is safe to wait at home?

Basically the only evidence that we have on waiting at home comes from the TermPROM study. Women who were randomly assigned to the expectant management groups were given the choice of waiting in the hospital, or returning home to wait for labor to begin there.

Out of the entire study, 653 women decided to go home, and 1,017 decided to stay in the hospital. It’s important to remember that before the women went home, they were evaluated, had a non-stress test, and roughly a third had vaginal exams, which likely increased their risk for infection.

The researchers found that there was an increase in some risks among women who waited for labor to start at home.

Compared to women who stayed in the hospital, women who waited at home were:

- More likely to have chorio (10.1% vs. 6.4%)

- More likely to receive antibiotics (28.2% vs. 17.5%)

- More likely to give birth by Cesarean (13.0% vs. 8.9%)

More babies born to mothers who waited at home received antibiotics (15.3% vs. 11.5%) and had a NICU stay greater than 24 hours (13.0% vs. 9.1%).

Certain factors increased some of these risks. Mothers giving birth for the first time who waited at home were even more likely to need antibiotics before delivery. Mothers who tested negative for GBS were more likely to need a Cesarean if they waited at home. Despite these increased risks, more women reported being satisfied with their care when they waited for labor at home (Hannah et al., 2000).

Because the evidence we have is limited, the benefits and risks of waiting at home are not clear. In the next section, we will talk about a recent, large study in which women waited for up to 48 hours for labor to begin. However, these women waited in the hospital, and they received antibiotics immediately if they were GBS positive, or at 24 hours for everybody else (See below).

Is there any other evidence that we should know about?

In 2014, Pintucci and colleagues published a very important prospective research study in which they followed 1,315 women with term PROM (Pintucci et al., 2014).

The women in this study waited for labor to begin for up to 48 hours unless there was a medical reason for induction.

Women were not allowed to be in the study if they were already in active labor, had a baby in breech position, or a high-risk condition such as diabetes or high blood pressure. A vaginal exam was done on entry into the study to confirm that membranes had released, to make sure there wasn’t a cord prolapse, and to check the cervix. Every six hours, the mother’s temperature was taken, a non-stress test was done to check the baby, and amniotic fluid was examined. The fetal heart rate was monitored every two hours.

Antibiotics were started after 24 hours of ruptured membranes, immediately if the woman was GBS positive, or if she developed any signs and symptoms of chorio (fever, meconium staining, fast heart rate in the mother or baby). Labor was induced at 48 hours (using oxytocin, prostaglandin gel, or both depending on cervical score) if it had not begun on its own.

The women whose labors began on their own had a 2.5% Cesarean rate, and the women who were induced had a 15.5% Cesarean rate (overall rate 4.5%).

The authors conclude that women who were induced at any time point had 6.8 times the odds of having a C-section compared to women who had expectant management.

However, these results should be interpreted carefully—women were only induced if they had medical reasons for an induction (such as infection), so this may explain why the C-section rate was higher in that group. The length of time from rupture of membranes to birth was not related to Cesarean section in this study.

If you recall, the overall rate of chorio in the TermPROM study was 6.7% (Seaward et al., 1997). In the Pintucci et al. study that included screening and treatment for GBS, the overall rate of chorio was 1.2%– in a sample that included many women who waited for labor to begin on its own (Pintucci et al., 2014).

The newborn infection rate was 2.5%. Newborn infection was defined as having at least one of the following: a low blood leukocyte count, high or low neutrophil count, elevated C-reactive protein (a measure of inflammation), or two or more symptoms such as vomiting, low temperature, fever, blue color, not breathing, fast breathing, trouble breathing, or high blood sugar.

When they only looked at babies born more than 24 hours after PROM, the rate of infection increased slightly to 2.8%.

Mothers who developed chorio or had more than 8 vaginal exams during labor had anincreased risk of having a newborn with an infection.

The results from the Pintucci study are important, because this is the first study to look at women with term PROM who had modern testing and treatment for Group B Strep. Basically, the results showed this group of women was able to wait for labor to begin on its own, with very good outcomes for both mothers and babies.

Why are most women in the U.S. induced when their water breaks at term?

In 1997, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended that women with term PROM be offered the option of inducing labor or waiting 24-72 hours for labor to start on its own. ACOG stated that there was “Level A evidence” (highest level of evidence) for this recommendation.

But in 2007, ACOG reversed this opinion and recommended that women with PROM at term should be induced immediately. Again, they said there was Level A evidence, or the highest level of evidence, for this new recommendation.

But the same research evidence (from the exact same research studies) was used to support both the 1997 and the 2007 statements.

The consequences of the new guideline were strong. Many women in the U.S. who experienced term PROM went from being offered the option of waiting for labor or inducing labor immediately, to now being told they “must” be induced.

But why did this happen? Why did ACOG’s stance change from 1997 to 2007, if no new research was used to support these changes?

We don’t really know the answer to that question. But as Mayri Sagady Leslie, CNM, MSN, EdD wrote in a 2009 blog article on Science and Sensibility (Leslie, 2009):

“Bulletin number 80 was released. The recommendation was changed… Now, this powerful “guideline” – which drives industry standards, institutional policies and procedures, medical school education, and, potentially, legal judgments – allows for just one option for mothers in this normal physiological condition: induction.”

Is it safe for women to wait for labor to begin on its own, if that is what they prefer?

The current evidence that we have suggests that mothers who experience term PROM should be counseled as to the potential benefits and harms of both induction and expectant management, so that they can make the choice that is most suitable for their unique situation.

Inducing labor for term PROM is a valid, evidence-based option for most women. At the same time, waiting for labor to start is also a valid, evidence-based option for most women. The mother’s values, preferences, and goals should always be taken into account when discussing her treatment options.

The TermPROM authors concluded, “Induction of labor with intravenous oxytocin, induction of labor with vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel, and expectant management are all reasonable options for women and their babies if membranes rupture before the start of labor at term, since they result in similar rates of neonatal infection and cesarean section.”

The American College of Nurse Midwives states that women with PROM at term should be informed about the risks and benefits of expectant management versus induction, and that if women meet certain criteria they should be supported in choosing expectant management as a safe option.

The criteria in the ACNM position statement include:

- A term, uncomplicated, pregnancy with only one fetus and with clear amniotic fluid

- No infections including Group B Strep

- No fever

- Normal fetal heart rate

- No vaginal exam at baseline, and then vaginal exams are to be kept to a minimum during active labor

What’s the bottom line?

- Having labor induced with oxytocin may lower a mother’s chances of experiencing infection, but does not have an effect on the C-section rate or on newborn infections

- One of the single most important ways to prevent infection after your water breaks is to avoid vaginal exams as much as possible during labor

- As long as both mother and baby are doing well and meet certain criteria, waiting for up to 2-3 days for labor to begin on its own is an evidence-based option. At the same time, induction is also an evidence-based option

- In today’s era with access to antibiotics if needed, the “24-hour clock” for giving birth is no longer based on evidence

Other Resources

Many parents have concerns about whether or not their infant will need extra blood tests or antibiotics after PROM, or after chorioamnionitis. To read the American Academy of Pediatrics paper about this issue, click here.

The best review article that we found on PROM actually came from this amazing textbook, called “Best Practices in Midwifery,” written by CNM faculty at Frontier Nursing University.

To read an interview with Rebecca about the topic of Term PROM, click here.

References:

- Akyol, D., Mungan, T., Unsal, A., et al. (1999). Prelabour rupture of the membranes at term–no advantage of delaying induction for 24 hours. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol, 39(3), 291-295. Click here.

- Ayaz, A., Saeed, S., Farooq, M. U., et al. (2008). Pre-labor rupture of membranes at term in patients with an unfavorable cervix: active versus conservative management. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol, 47(2), 192-196. Click here.

- Burchell, R. C. (1964). Premature Spontaneous Rupture of the Membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 88, 251-255. Click here.

- Calkins, L. A. (1952). Premature spontaneous rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 64(4), 871-877. Click here.

- Casanueva, E., Ripoll, C., Tolentino, M., et al. (2005). Vitamin C supplementation to prevent premature rupture of the chorioamniotic membranes: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 81(4), 859-863. Click here for free full text.

- Conway, D. I., Prendiville, W. J., Morris, A., et al. (1984). Management of spontaneous rupture of the membranes in the absence of labor in primigravid women at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 150(8), 947-951. Click here.

- Dare, M. R., Middleton, P., Crowther, C. A., et al. (2006). Planned early birth versus expectant management (waiting) for prelabour rupture of membranes at term (37 weeks or more). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(1). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005302.pub2 Click here.

- Ezra, Y., Michaelson-Cohen, R., Abramov, Y., et al. (2004). Prelabor rupture of the membranes at term: when to induce labor? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 115(1), 23-27. Click here.

- Gunn, G. C., Mishell, D. R., Jr., & Morton, D. G. (1970). Premature rupture of the fetal membranes. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 106(3), 469-483. Click here.

- Hallak, M., & Bottoms, S. F. (1999). Induction of labor in patients with term premature rupture of membranes. Effect on perinatal outcome. Fetal Diagn Ther, 14(3), 138-142. Click here.

- Hannah, M. E., Hodnett, E. D., Willan, A., et al. (2000). Prelabor rupture of the membranes at term: expectant management at home or in hospital? The TermPROM Study Group. Obstet Gynecol, 96(4), 533-538. Click here.

- Hannah, M. E., Ohlsson, A., Farine, D., et al. (1996). Induction of labor compared with expectant management for prelabor rupture of the membranes at term. TERMPROM Study Group. N Engl J Med, 334(16), 1005-1010. Click here for free full text.

- Hannah, M. E., Ohlsson, A., Wang, E. E., et al. (1997). Maternal colonization with group B Streptococcus and prelabor rupture of membranes at term: the role of induction of labor. TermPROM Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 177(4), 780-785. Click here.

- Hill, M. J., McWilliams, G. D., Garcia-Sur, D., et al. (2008). The effect of membrane sweeping on prelabor rupture of membranes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol, 111(6), 1313-1319. Click here.

- Imseis, H. M., Trout, W. C., & Gabbe, S. G. (1999). The microbiologic effect of digital cervical examination. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 180(3 Pt 1), 578-580. Click here.

- Lanier, L. R., Jr., Scarbrough, R. W., Jr., Fillingim, D. W., et al. (1965). Incidence of Maternal and Fetal Complications Associated with Rupture of the Membranes before Onset of Labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 93, 398-404. Click here.

- Lenihan, J. P., Jr. (1984). Relationship of antepartum pelvic examinations to premature rupture of the membranes. Obstet Gynecol, 63(1), 33-37. Click here.

- Leslie, M. S. (2009). When Is Evidence Based Medicine NOT Evidence Based? Inductions for PROM at Term. Science and Sensibility: A Research Blog About Healthy Pregnancy, Birth & Beyond. 2014, from http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=507

- McDuffie, R. S., Jr., Nelson, G. E., Osborn, C. L., et al. (1992). Effect of routine weekly cervical examinations at term on premature rupture of the membranes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol, 79(2), 219-222. Click here.

- Moore, R. M., Mansour, J. M., Redline, R. W., et al. (2006). The physiology of fetal membrane rupture: insight gained from the determination of physical properties. Placenta, 27(11-12), 1037-1051. Click here.

- Morales, W. J., & Lazar, A. J. (1986). Expectant management of rupture of membranes at term. South Med J, 79(8), 955-958. Click here.

- Pietrantoni, E., Del Chierico, F., Rigon, G., et al. (2014). Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation during pregnancy: a potential tool to prevent membrane rupture and preterm labor. Int J Mol Sci, 15(5), 8024-8036. Click here for free full text.

- Pintucci, A., Meregalli, V., Colombo, P., et al. (2014). Premature rupture of membranes at term in low risk women: how long should we wait in the “latent phase”? J Perinat Med, 42(2), 189-196. Click here.

- Seaward, P. G., Hannah, M. E., Myhr, T. L., et al. (1997). International Multicentre Term Prelabor Rupture of Membranes Study: evaluation of predictors of clinical chorioamnionitis and postpartum fever in patients with prelabor rupture of membranes at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 177(5), 1024-1029. Click here.

- Seaward, P. G., Hannah, M. E., Myhr, T. L., et al. (1998). International multicenter term PROM study: evaluation of predictors of neonatal infection in infants born to patients with premature rupture of membranes at term. Premature Rupture of the Membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 179(3 Pt 1), 635-639. Click here.

- Shalev, E., Peleg, D., Eliyahu, S., et al. (1995). Comparison of 12- and 72-hour expectant management of premature rupture of membranes in term pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol, 85(5 Pt 1), 766-768. Click here.

- Shubeck, F., Benson, R. C., Clark, W. W., Jr., et al. (1966). Fetal hazard after rupture of the membranes. A report from the collaborative project. Obstet Gynecol, 28(1), 22-31. Click here.

- Spinnato, J. A., 2nd, Freire, S., Pinto e Silva, J. L., et al. (2008). Antioxidant supplementation and premature rupture of the membranes: a planned secondary analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 199(4), 433 e431-438. Click here for free full text.

- Taylor, E. S., Morgan, R. L., Bruns, P. D., et al. (1961). Spontaneous premature rupture of the fetal membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 82, 1341-1348. Click here.

- Veleminsky, M., & Tosner, J. (2008). Relationship of vaginal microflora to PROM, pPROM and the risk of early-onset neonatal sepsis. Neuro Endocrinol Lett, 29(2), 205-221. Click here.

- Xu, H., Perez-Cuevas, R., Xiong, X., et al. (2010). An international trial of antioxidants in the prevention of preeclampsia (INTAPP). Am J Obstet Gynecol, 202(3), 239 e231-239 e210. Click here.

- Zlatnik, F. J. (1992). Management of premature rupture of membranes at term. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am, 19(2), 353-364. Click here.